If you haven’t read the first post I did about addiction, I recommend you read that first HERE so you understand why I’m posting these articles.

This is written by the daughter of an addict. It’s real. It’s raw. It’s honest. Her father unfortunately never permanently overcame addiction and it eventually took his life.

Here it is:

“I’m the daughter of an addict.

That’s a pretty loaded sentence. So, maybe I should start at the beginning.

I have exactly two, blurry pictures of my father and I before the age of 9. I was an infant at our first official meeting and I was wearing a pink fuzzy romper. Even though it is out of focus, I’m pretty sure my father was smiling. The first time I remember meeting him, I was nine. It occurred to me halfway through my flight that I would be meeting my father and stepmother and that maybe a recent picture of him would have been nice, because I had no idea who I was looking for when I walked off the gangway. The reason it took nine years for me to really meet my father was because it took him that long to get sober. My father was an alcoholic.

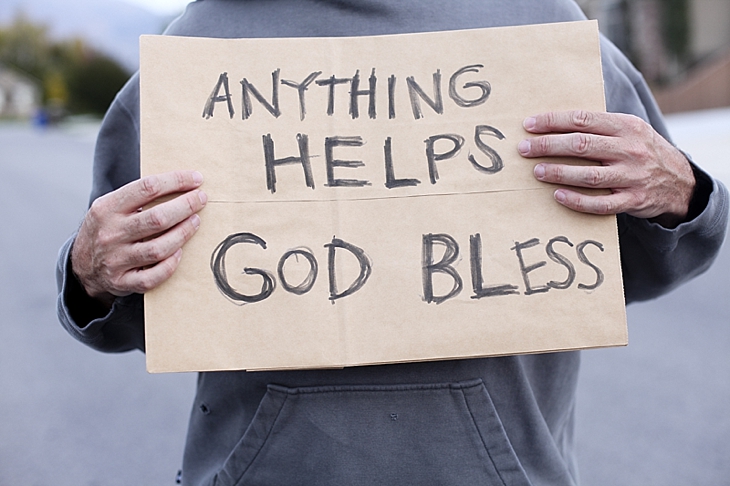

Often, growing up, my friends would ask why I don’t have a dad. By the time my friends knew to ask this question, I knew I couldn’t tell them the truth, because I was ashamed that I was made of the same stuff as an addict. I would tell them things like, “he’s fishing in Alaska”, or “he’s a spy” (very original, I know).

From the lies, stemmed a need for perfection. Best grades. Best athlete. Best friend. I was labeled “Type A”, and “competitive”. Most people said it would serve me well once I found “my” place to channel all that drive. Mostly, I thought that if I were perfect, no one would guess that my father was an alcoholic. My father was sober for about five years. I visited him during the summer and winter breaks from school. He was smart, adventurous, funny, and the only other person I knew that could talk as much as me. He taught me some of my favorite lessons, and made some of my favorite childhood memories with me.

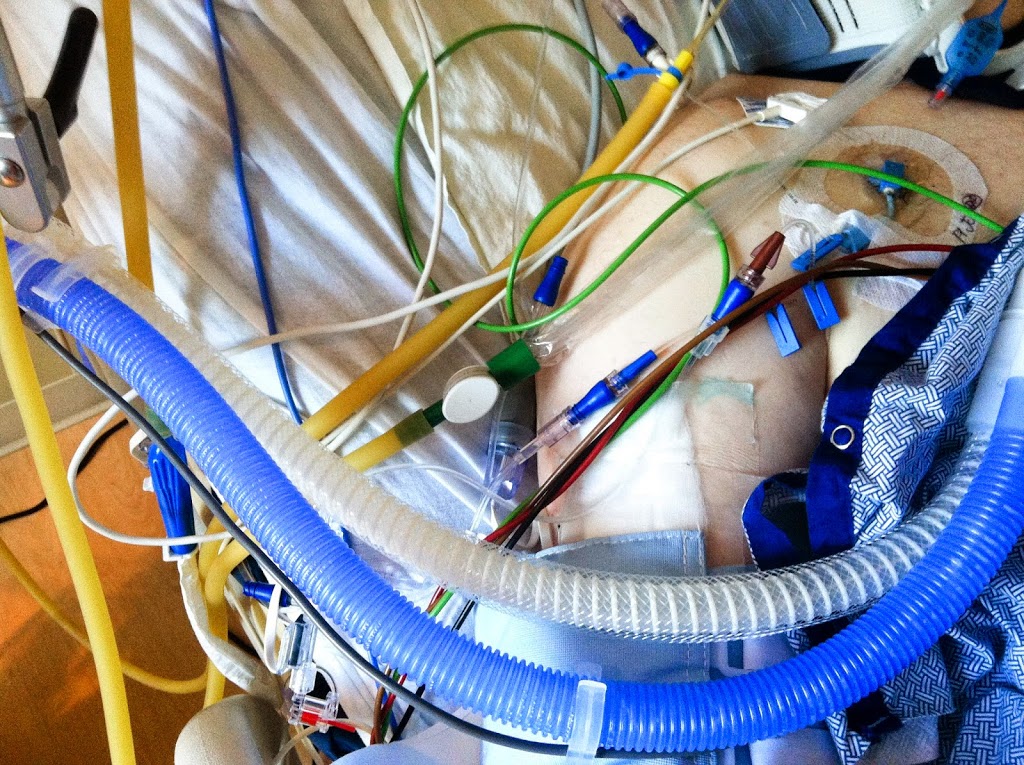

Then, when I was fourteen, I called him to wish him a happy birthday. Only, my step-mom informed me he didn’t live there anymore, and had started drinking again. Despite her and my mom’s words to the contrary, I was pretty convinced that I hadn’t been enough to keep him from drinking again. The perfectionism continued, because I couldn’t let anyone know that I was the daughter that wasn’t enough to keep her father wanting her. My “drive” became my biggest weakness in high school and I struggled with depression my senior year. I took on too much, slept too little to make it all work, and never told a soul that I felt out of control. Thankfully, my appendix burst about halfway through senior year and after I was released from the hospital, my (incredibly smart) mother informed me I’d be pulling the plug on most of my activities and learning to “chill”. It was a good thing, and a turning point for me.

I never saw, spoke to, or heard from my father again. He drank himself to death a few weeks before I turned 21. During his funeral I was angry. I was angry that there was so many people there that had so many stories to share about him and I had next to nothing. I was angry that I had spent so long being ashamed of his addiction – and there were so many people celebrating his life.

But mostly, I was relieved. I was relieved that I didn’t have to wonder where he was. Or wonder why he didn’t want to talk to me, or why he didn’t WANT me. I was also relieved that his troubles were over. One of my uncles (one of his brothers) said something very similar to me, the day after his funeral. It made me realize “Holy CRAPSTACKS! I’m NOT the only one who feels these things!” It seems small, and trivial, and in hindsight, obvious – that I’m not the only one who feels ashamed of addiction. Angry that someone they know is an addict. Not the only one who feels like they’re obviously not enough to keep someone from addiction. And, for me, and the loved ones of my father, relieved that he’s no longer troubled.

I’m forever affected by the title “daughter of an addict”. But it’s better now. I can use it for good. I can have real and honest conversations with my kids about addiction. I can own me and my feelings better now. I’m more confident, secure, and able to give more to the world than ever before. That is why I said yes to Lindsay’s request to write about my father’s alcoholism and how it affected me. Maybe this can be the uncle that says “me, too” for someone. If not, well, it was good to get it all off my chest anyway.”